Maus: A Unique and Insider’s Way of Narrating the Holocaust

It is not easy to even discuss the experience of writing about the Holocaust. There are many works penned by and based on the testimonies of those who lived through this phenomenon directly. Their children and grandchildren continue to keep this legacy alive, both through academic studies and other forms of creative work. Today, even with a vast body of literature on this subject, which has now become a field in its own right, there can still be points that have not been sufficiently addressed on an emotional level or brought into full consciousness. Moreover, the debates have lost little of their intensity, as current political developments constantly require us to remember and discuss the historical past.

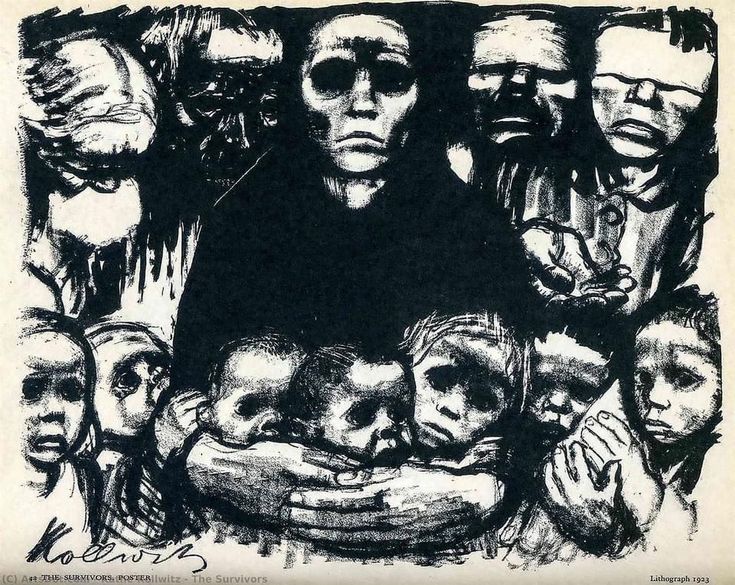

I feel my consciousness and my soul are profoundly inadequate in understanding the mass persecution people endured, and its effects and consequences. This feeling of inadequacy has been the primary obstacle preventing me from writing on this topic. From a personal perspective, perhaps I only have the right to say this: even the slightest contact with a small portion of Holocaust literature creates a deep sense of pain, injury, and fatigue in the human soul. For example, even a brief encounter with testimonies written in the simplest language caused an emotional disconnection, reaction, and a sense of being paralyzed in me. In such moments, I must admit that I sometimes felt breathless and had a strong desire to escape from those pages.

During my personal Holocaust research in the winter of 2025—which was a rather limited and modest endeavor—I encountered works that I struggled to finish. There were many times I had to put a book down. On cold winter days, I often found myself staring blankly at the snow-covered surroundings, feeling no motivation to do anything, and experiencing moments when I was ashamed of being human. The reason I state this so concretely is to convey the heavy impact that even an indirect witnessing of this experience can have on the human spirit. I do not think people who have not researched the subject are fully aware of this, which is why it needs to be written about. Witnessing this level of violence, even decades later, can be considered a form of trauma. In the literature, as far as I know, this is referred to as “secondary trauma.” Therefore, I can say that Holocaust historians and researchers operate under a significant psychological burden. This is a special kind of violence, and the dehumanizing violence we encounter in the Holocaust—the rationalization of violence and its integration into routine—is on a completely different level that the human mind and soul cannot accept. Nevertheless, it is an obligation to carry this experience into the future by incorporating it into today’s reality and to keep the “memory” alive. This is vital both for coping with the trauma and for being able to respond correctly when faced with the political reflections of this phenomenon, which belongs to history but remains alive today through its effects.

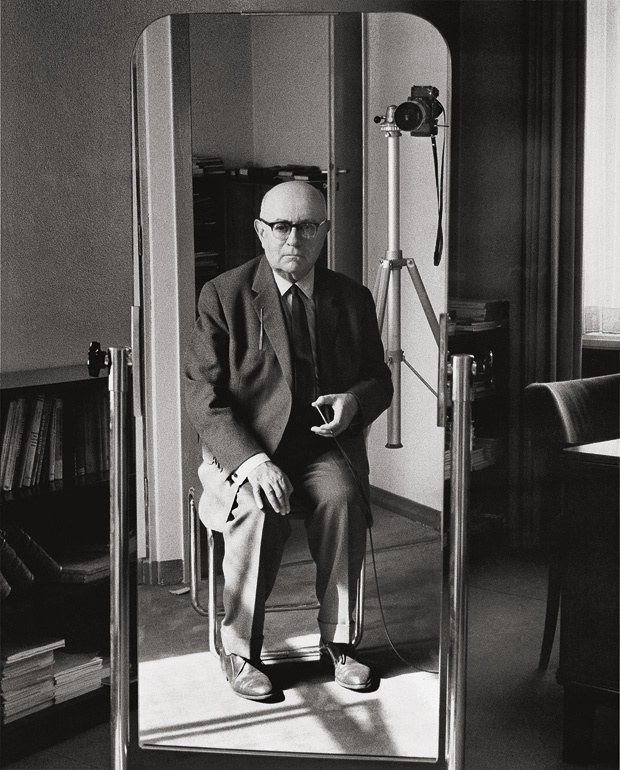

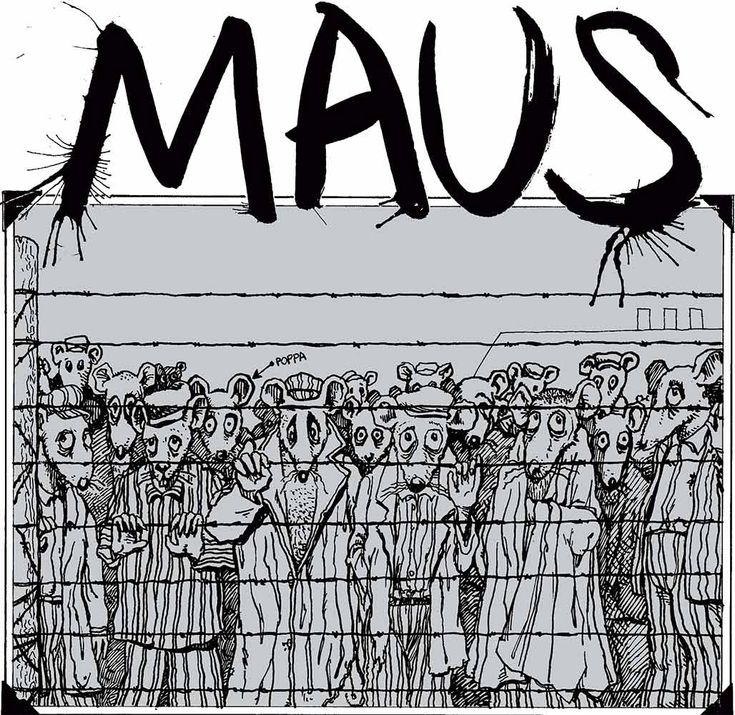

In a previous article, I wrote a critique of Peter Weiss’s play, “The Investigation.” In his work, Weiss aimed to convey documentary-historical reality to society in a unique and creative way by touching upon memory. However, Art Spiegelman’s Maus constitutes a unique exception in this field, as far as I am aware. This difference, in my opinion, stems not only from the author’s mindset and method but also from other factors. Spiegelman conveys what is perhaps the most horrifying and difficult-to-verbalize event in human history using a powerful allegorical narrative. The originality of Maus comes from its extraordinary naivete and simple honesty in its manner of narrating the unnarratable, like the Holocaust. This approach, I believe, has created a new methodology poised to become a fundamental reference point in the field of Holocaust education.

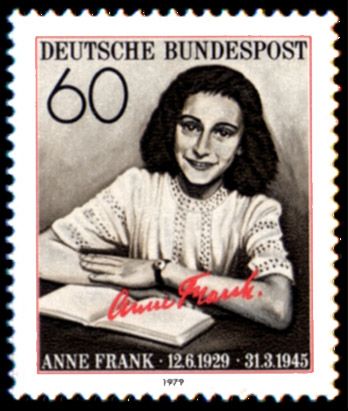

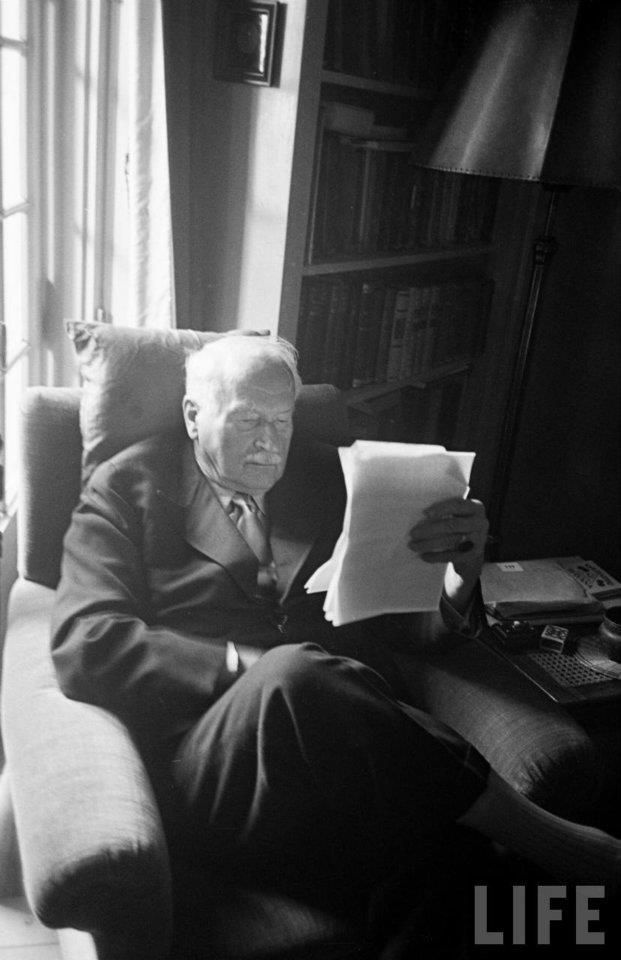

Spiegelman’s narrative begins with him asking his father, who lives in America, to tell him about their family history and the reality of the Holocaust. The author’s father is depicted as a grumpy old character who, after the early death of his wife, remarried but can never quite hide his unhappiness and disappointment. In this respect, at first glance, he resembles many father figures in our society and seems to have no remarkable features. However, as the author begins to narrate the story of his mother, Anja, whom he never knew, and his brother, we are slowly drawn into this unbearable tragedy. The Spiegelman family was one of thousands of Jewish families living in the Czech Republic and Poland until the 1930s. Vladek Spiegelman had a successful and happy marriage with Anja, the daughter of a wealthy family, and built his own future and family. His business in the textile industry was doing well, and he had a child. This ordinary family portrait would be shattered to pieces when the horrific changes in Nazi Germany reached Poland.

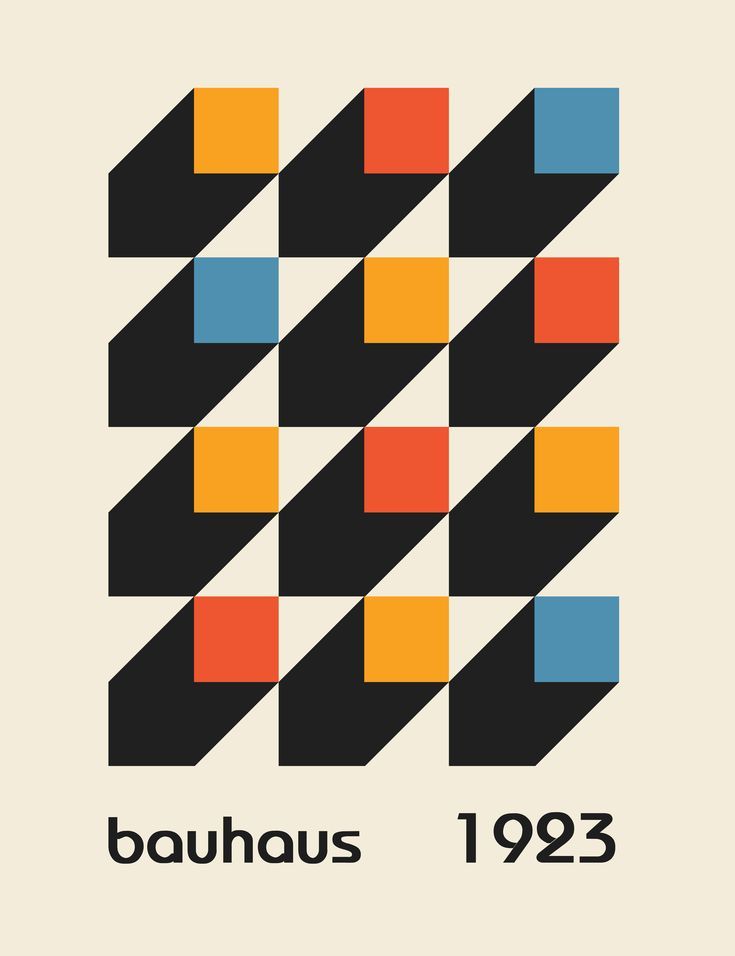

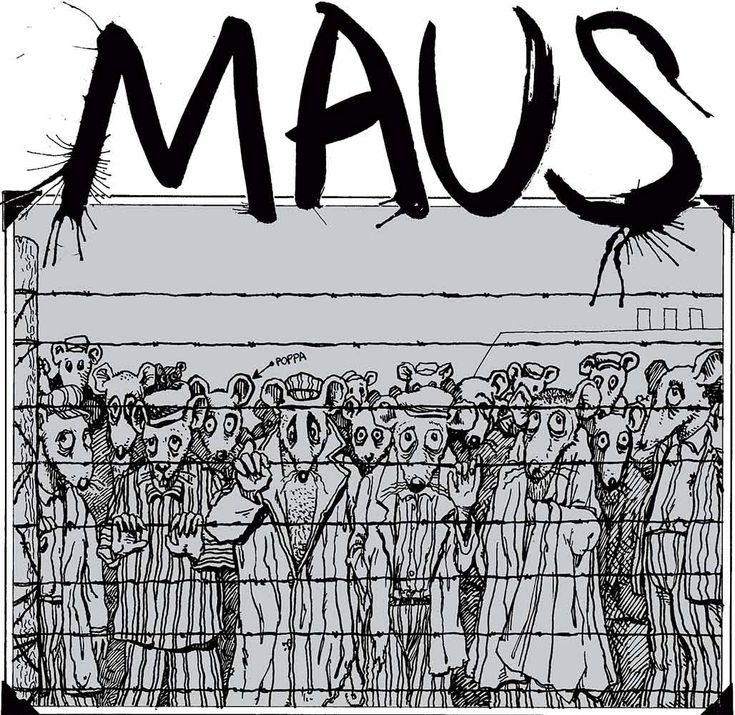

This change began to rapidly transform all layers of social life, step by step separating people who had previously lived together. The two distinct ethnic groups, Jews and Poles, were gradually segregated by invisible yet sharp lines. In this process, people became alienated from one another, and hatred and intolerance became commonplace, so much so that these feelings even seeped into the lives of the youngest children. Eventually, the Spiegelman family was also affected by this process. First, they lost their businesses and assets, becoming increasingly excluded from social life. During the German occupation of Poland, Vladek Spiegelman was taken prisoner by the Germans. Upon his return, his father-in-law told him that his factory had been confiscated. Dispossession was the first step in the exclusion from social and economic life in this process. The purpose of this transfer of capital, implemented by the Nazis as part of the Nazification of society in occupied countries, was to push the Jews completely outside the political and legal superstructure. This rendered the Jews vulnerable, disconnected, isolated, and powerless. It was clear that this first step would be followed by other processes that would slowly lead them to the concentration camps. Today, there is a common misconception that the National Socialists sent the Jews directly to concentration camps. However, this was a long and extremely painful process. The concentration camp was the final and most horrifying stage of this process. This is also evident in the Spiegelman family’s story. Before the Auschwitz-Birkenau camps, Polish, Hungarian, and other European Jewish families were subjected to great persecution. They were torn from their homes and families and forced to live for long periods as homeless people in hiding. Their lives before being sent to the concentration camps were spent in constant fear and poverty.

The most fundamental problem was the lack of any legal guarantee for their lives. In countries where people were encouraged to inform on one another, they concealed their identities and appearances under various guises. The Spiegelman family went through a similar process before being taken to the concentration camps. A large part of the family perished in the camps. Although the author’s parents survived the Holocaust, their emotional and social relationships were never the same again. Indeed, it is a known fact today that the families of Holocaust survivors often struggle with numerous emotional disorders. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, anxiety, and fear of abandonment are just a few of these conditions. These problems are passed down through generations and can be triggered by external factors such as wars, major social events, or political conflicts.

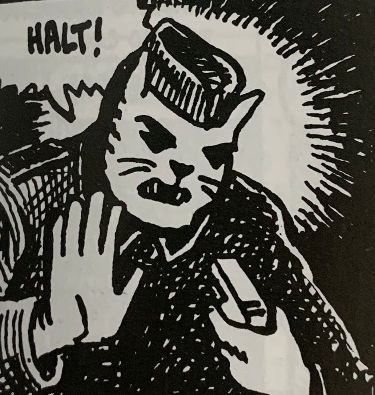

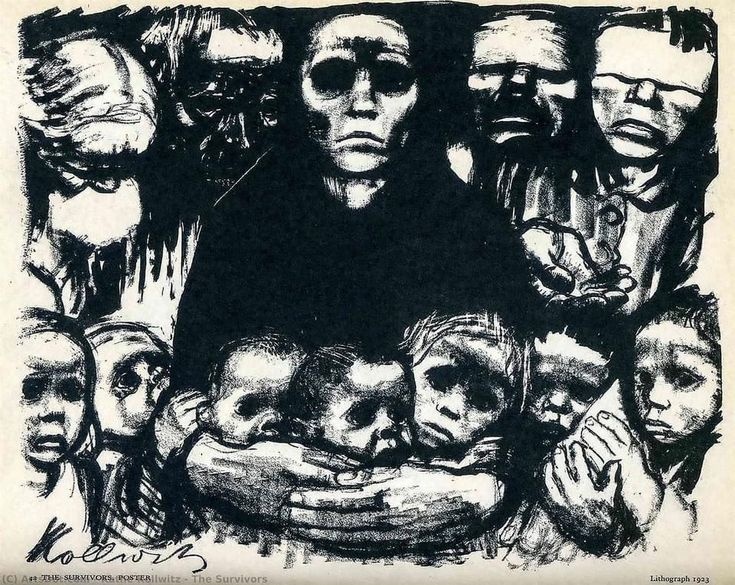

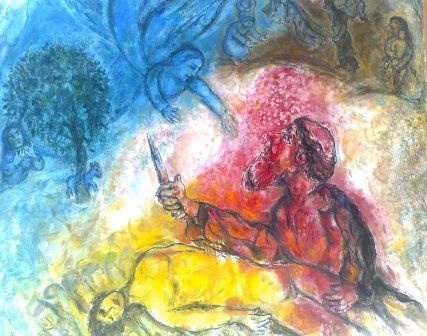

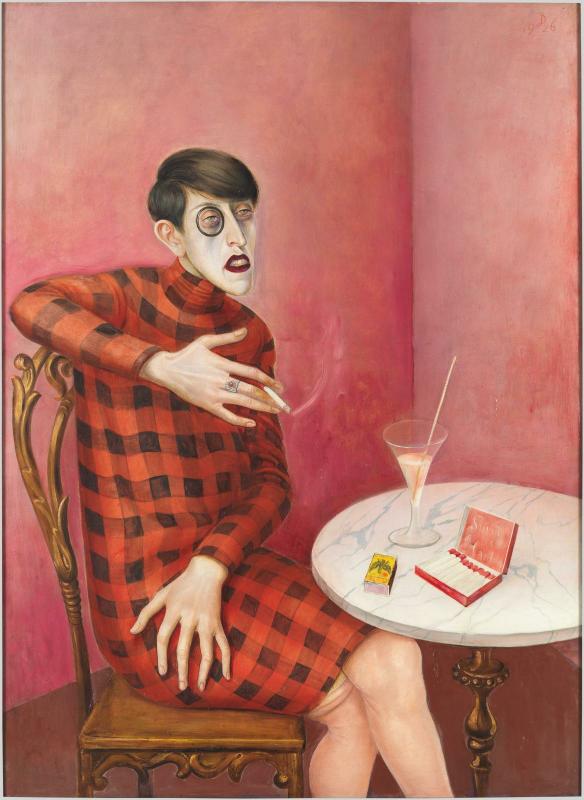

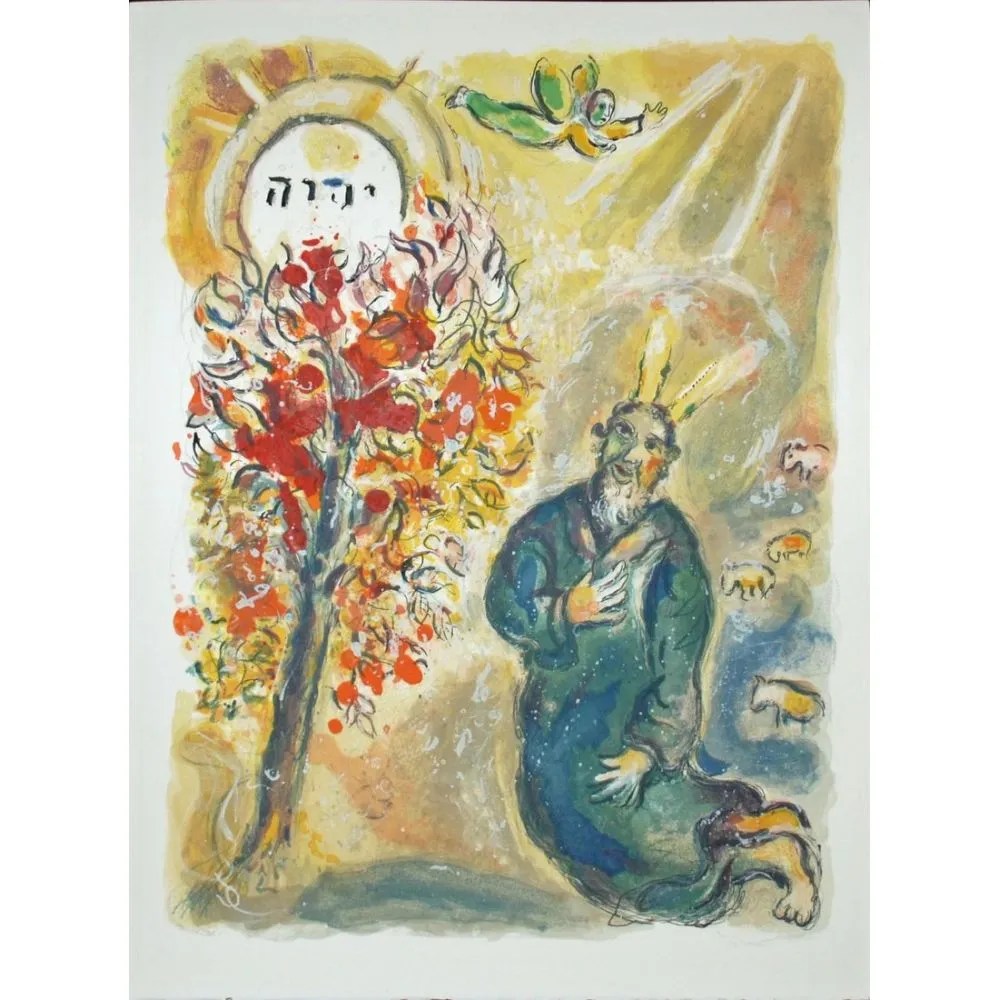

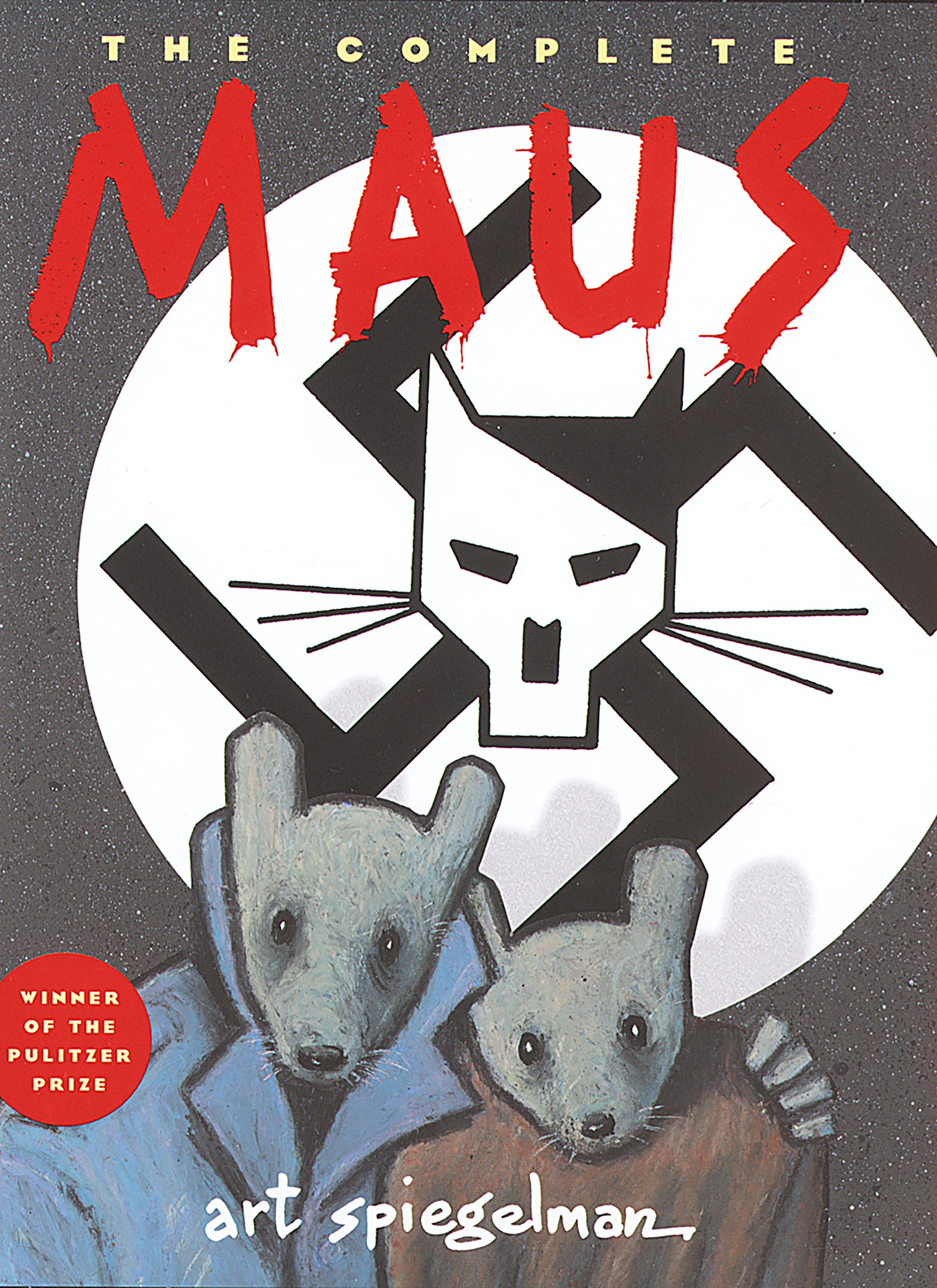

In his work, Spiegelman uses a highly symbolic visual representation, depicting Germans as cats, Poles as pigs, and Jews as mice. This choice is deliberate. Nazi propaganda likened Jews to disease-carrying “rats” to exclude them from society and legitimize their extermination. Spiegelman, however, inverts this hateful propaganda by drawing Jews as hunted, defenseless, and small “mice.” This is a powerful artistic counter-stance that emphasizes the innocence and helplessness of those whom the Nazis tried to dehumanize. The depiction of Germans as “cats” is not an attempt to make them appear cute, but rather a metaphor that exposes the cruel power imbalance between predator and prey. The absolute dominance of the cat over the mouse, and its tendency to play with it before killing it, symbolizes the arbitrary and cruel dominion of the Nazis over their targeted groups. The cat mask represents not cuteness, but predation and power. The success of Maus lies precisely at this point: in its ability to convey the social roles and the brutal reality behind the masks in the most striking way.

Title: A Survivor’s Tale: Maus

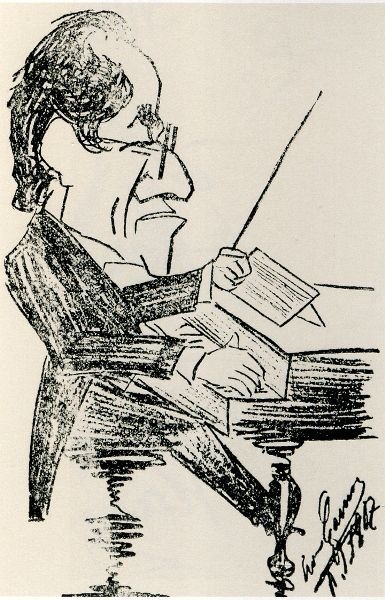

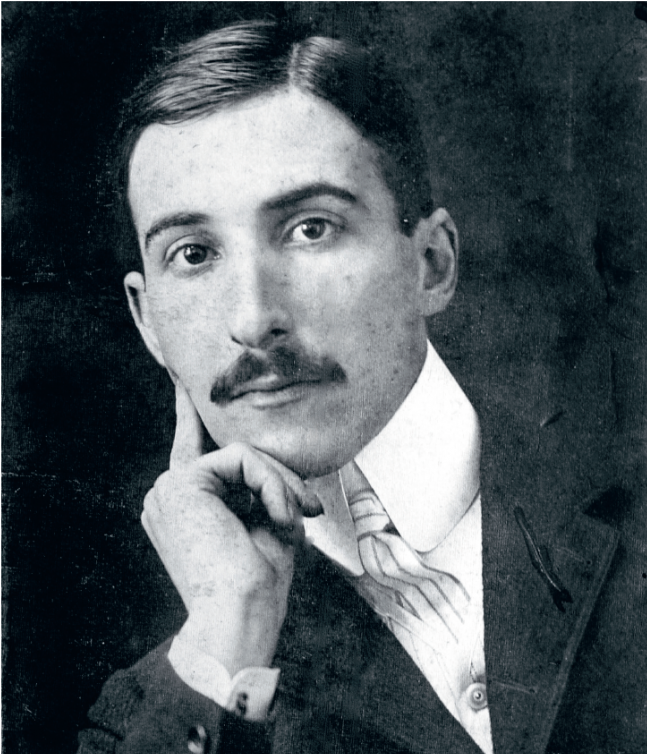

Writer/Illustrator: Art Spiegelman

Translator [of the Turkish edition]: Ali Cevat Akkoyunlu

Editor [of the Turkish edition]: Levent Cantek

Edition Reviewed: 2004, İletişim Publishing, Istanbul.

Critic: Onur Aydemir

Date: 21.04.2025, Ankara

● ONUR AYDEMİR ●

● 2025, ANKARA ●

First published on the Flanörün Günlüğü website